Belinda’s Ongoing Story, as told by Larry Wurn.

Although we had been married twenty years, we never had the time to take the honeymoon I had promised my bride two decades earlier. Belinda wanted to visit India and Nepal. I had visited these countries in my 20s, courtesy of a photo and book assignment I had done for an art museum.

Nepal was inaccessible to Westerners due to a heavy-handed Chinese invasion and the resulting instability in the capital city, Kathmandu. Instead, we visited nearby Bhutan, a country dubbed “Shangri-La” due to its mountainous vistas and its King’s avowed focus on “Gross National Happiness” over “Gross National Product.”

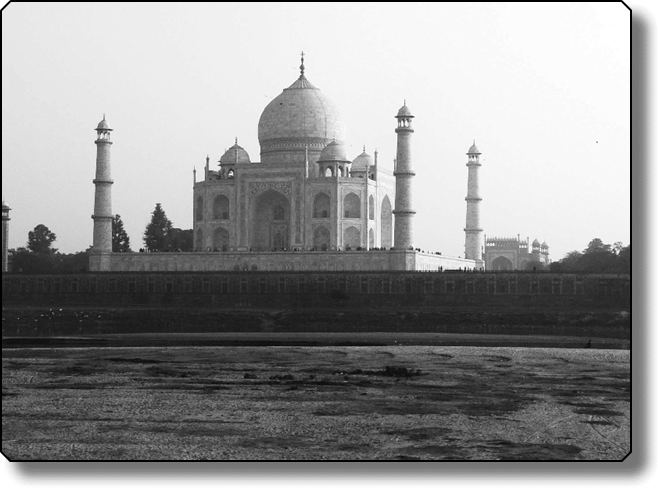

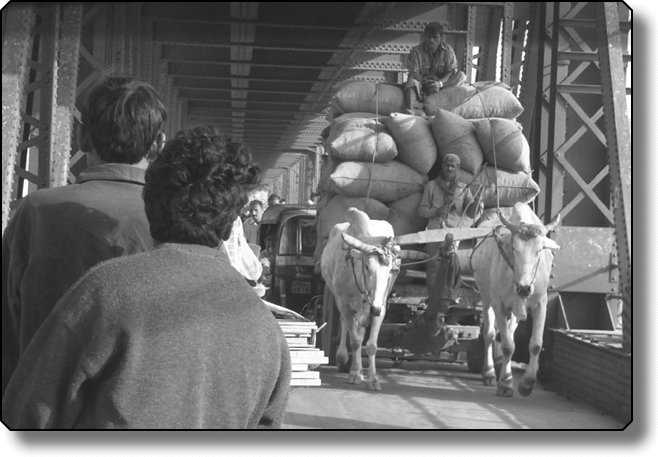

After a week in Bhutan, we moved down to India. It had always been Belinda’s dream to see the Taj Mahal, so after a short visit to Delhi, we drove down to Agra, the site of that magnificent edifice. The four hours of traffic surrounded us with every method of transport imaginable: ancient, hand-carved oxcarts, camels, elephants, cows and monkeys wandered among the cars, tractor-trailer trucks, and three-wheeled vehicles of every description; it was both slow-moving and remarkable. Belinda and I have always enjoyed expanding our minds by immersing ourselves in either nature or totally different cultures from our own, from time to time. We find the experience both challenging and enriching to our bodies, minds and souls. Along the way, we passed numerous medical clinics.

Unfortunately, that night brought problems. Belinda found herself unable to eat or pass foods — both classic signs of a total bowel obstruction. This was quite distressing. She had just undergone a small bowel obstruction surgery by an excellent surgeon six months prior, her first gut surgery since she had pelvic surgery and massive amounts of radiation therapy for cervical cancer over 20 years prior.

A physician who came to our hotel room inserted an NG tube into her stomach through her nose, then hooked her up to intravenous feeding, fluids and pain medication. On that day, Belinda rolled back and forth, trying to get food to pass through. I treated her, but this time things went very differently. During treatment, both of my hands were pulled toward a single point in her intestines that felt hard and hot. It felt like an infection.

This presented a significant problem. While we felt our work decreasing adhesions in the pelvis might help clear a bowel obstruction, our therapy is contraindicated in cases of active infection. Since we are treating fascia that includes the interstitial spaces (between muscles and organs), we avoid treating infected areas because that could create an opportunity for the infection to spread.

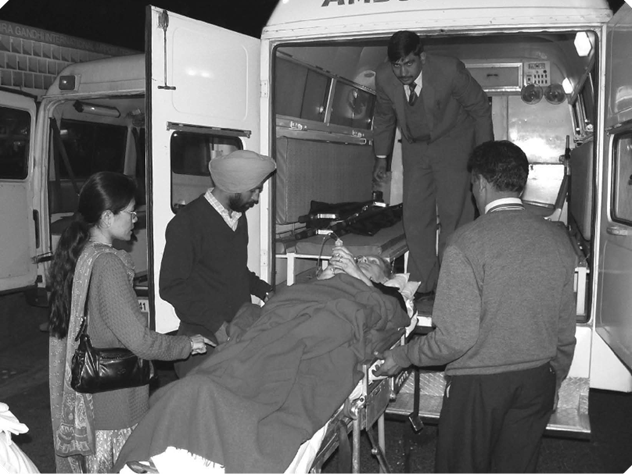

Belinda lay there for three days, hoping that the obstruction might just be a spasm that would release, allowing food to pass, meaning she could avoid bowel surgery. With each day, she was becoming weaker. Finally, we decided to move her to a hospital.

Ultimately, we decided to life-flight Belinda to Delhi, where we hoped to find a modern hospital. Agra did not have the facility to handle her complex situation. The flight helped us avoid the elephants, camels, oxcarts, and large potholes in the road between Agra and Delhi. Still, the physician who accompanied us had the pilot maintain a low altitude.

“So your wife doesn’t explode from the low pressure at high altitudes,” she said.

That was when we realized that this situation would resolve in India – not at home with our physicians and modern hospitals. On the way to the airport, the ambulance driver was kind enough to divert his route to a promontory across the river from the Taj Mahal. Belinda could fulfill part of her childhood dream to see this lovely edifice – a testament to another husband’s deep love for his wife centuries ago.

I began to cry softly, thinking of our life journey and the love that has persisted through all the trials and traumas of our lifetime adventure. With all the traumas Belinda has undergone, we both still feel very blessed by the gift of our lives, the therapists, patients, physicians, and scientists we worked with – so many of whom have become friends or touched our lives deeply as we have touched theirs.

After the emergency flight to Delhi, we were transported to a disgusting and filthy facility that was reported to have excellent physicians. I moved Belinda to the Apollo Hospital, which was much cleaner and more modern. The Boston-trained physician was aware of our work and was patient as I continued to try to clear the blockage. Still, we continued to feel a single site with increased temperature.

Remembering Belinda’s difficulty with the previous post-surgical infection, it made sense that the culprit was likely a persistent infection from that bowel surgery. In the end, Belinda elected to undergo her second bowel resection surgery.

They took Belinda to the operating room at 5:30 in the morning. I was not allowed to join her, but at 8:30, an orderly came in to fetch me. He spoke only Hindi, even though English is the common language that unites India. He was very animated, gesturing for me to follow him. His only explanation, and apparently his only English, was, “come, sir.”

The trip downstairs was other-worldly and sometimes nightmarish. As we arrived at the ground floor, we kept following two arrow signs, always going in the same direction. One read “Surgery;” the other read “Morgue.”

As we finally reached a very long corridor, they were wheeling a dead body from the area, covered by a sheet. Part of me wanted to lift the sheet to see if it was Belinda; another part of me didn’t want to know.

Like being in an “Alice in Wonderland” dream, we passed a small hospital wing whose entrance sign read: “Test Tube Baby Unit.” I am sure they have good doctors there, but the wording of the sign and the feelings it evoked in me seemed strange to my Western mind.

At last, we arrived at the end of the hall where we faced the (now familiar) two signs, now giving very different directions. The “Surgery” sign pointed to the left and the “Morgue” sign to the right.

My guide picked this moment to stop, breathe, and catch his breath from our long trek.

It was the longest moment of my life.

At last, he stepped to the right, turned and put out his hand, indicating that I should go left into the surgical suite.

I began to breathe again.

He had me scrub in, put on a surgical cap, gown, and booties, and enter the main surgery room. The room was wide open, about 30 feet square, with eight people being operated on simultaneously. Looking around at this scene in awe, I saw someone gesturing to me from the third table on the right. It was Belinda’s surgeon.

Slowly I approached the table. There was my love. She was totally anesthetized on her back, with a mound of bright red intestines piled up on her rib cage. The doctor started moving her bowels around with his hands to show me what he found. “See,” he said, “No adhesions; you did a remarkable job with her. This entire abdomen should be totally packed with adhesions by now.” It was amazing to see that there were no adhesions at all in an area that had been so severely burned by radiation therapy 30 years before.

“So, what is the problem,” I asked.

“It’s a problem from the prior bowel surgery,” he said. “So often, the problem is post-surgical adhesions, but that’s not it in this case.” He lifted a section of the intestines for me to see. There, like a wedding band or the gold label on a cigar, a tight infected band encircled her intestines in a vice-like grasp, decreasing the 1½ inch (4 cm) diameter of her intestines to a tightly banded closure about a half-inch in diameter. The yellow-green color of the band indicated a state of severe infection.

“It’s good we operated now,” the surgeon told me. “Otherwise, this would have burst the intestine, causing infection to spread throughout the abdomen and pelvis.” He proceeded to cut out the infected area and rejoin the cut sections.

As it happened, Belinda’s physician was an excellent surgeon. She healed without infection this time, despite the proximity of seven other open surgeries of various types that surrounded us.

When Belinda and I met with the surgeon afterward, he offered some words of wisdom.

“There is nothing you could have done to treat the infection, but you really did a remarkable job clearing adhesions in Belinda’s abdomen and pelvis. The fact that you could clear all of the adhesions that must have been there, considering her history, leads me to believe that you can delay or prevent surgery in people with partial bowel obstructions. I encourage you to explore that area; you may be able to relieve much suffering and hardship.”

Post-script to the story:

After spending a couple of weeks recovering in the hospital, and having totally missed most of our delayed honeymoon, Belinda and I asked permission to move to a different hospital. “We’d like to be near a historic site or a beach,” we said. “Do you have a sister hospital we could move to for our final days in India before our flight home?”

“Oh, yes,” the Administrator said. “We have an affiliate hospital on the Southeast coast, in Chennai. I could move you there Monday.” It was Friday night, Christmas eve. Christmas was coming Saturday, and there was no flight Sunday, so we arranged for the first flight out to Chennai on Monday morning.

Sunday (the day before our flight), the Tsunami hit India, making its greatest landfall at Chennai. I would have been on the beach when it crashed at 9:30 that morning since I always rise early and go to the beach when we are near one. Belinda would have become a very low-priority patient among the survivors of the 53,000 people who died there that day.

Blessed as we were to avoid that massive tragedy, a catastrophe of global proportions, we moved on to the city of our departure, Mumbai. After having Belinda in the hospital for over three weeks, I splurged and got us a room at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai. This hotel was a magnificent edifice — one that was recently attacked and burned as a target of terrorists using automatic weapons and hand grenades. Over 200 people died in the Mumbai attacks, which targeted Western tourists.

I guess you just have to live your life each day knowing that “this is it.” The moments we spend in life are all we have, each of us. Each of us needs to make the not a best of the time we have here on earth.

Life is not a dress rehearsal.

—

Get the Natural Small Bowel Obstruction Help that You Need

Our Clear Passage Approach is a non-surgical therapy that has been shown in numerous medical journals to decrease adhesions in the abdomen and pelvis, returning a more pain-free and functional quality of life.

If you or anyone you know is suffering from adhesions, we encourage you to complete a contact form, call us at 1-352-336-1433 or email us at info@clearpassage.com.

You will be able to schedule a phone consultation with one of our certified therapists at no cost and learn whether our non-surgical treatment is appropriate for you. The treatment, which can feel like a deep, site-specific massage, can be completed in five days (M-F) in several cities in the U.S.A. and the U.K.

Related Content:

Research and Success Rates

- Study Results for a Non-Surgical Bowel Obstruction Treatment

- Study Results for a Non-Surgical Bowel Obstruction Treatment

- Bowel Obstruction Success Rates

Questions Answered

- Recurring Small Bowel Obstruction Treatment Frequently Asked Questions

- The Most Common Causes of Bowel Obstruction and How to Prevent It

- Bowel Blockage Symptoms

- How to Prevent Bowel Obstruction

- Can Diverticulitis Cause Bowel Obstruction?

- Seven Signs of Intestinal Blockage

- What to know before accepting an IBS Diagnosis

- How Long Does a Bowel Obstruction Last?

- What is the Cause of a Small Bowel Obstruction and What Are Your Options for Treatment?

- How Will My Lifestyle Change with Small Bowel Obstructions?

- Is There a Natural Treatment for Small Bowel Obstruction?

- What SBO Patients Can Expect From Treatment

Treatment

- At a Glance: Bowel Obstruction

- Bowel Obstruction

- Bowel Obstruction – Need Help Now?

- Bowel Obstruction Treatment

- [Infographic] The Main Causes of Bowel Obstructions

Patient’s Stories

- Bowel Obstruction: Patient Story Update

- Video Testimonial – A Mother’s Journey to Recovery: Small Bowel Obstruction

- What Is Bowel Obstruction? – A Patient’s Perspective

- A Glimpse into a Brave Young Boy’s Journey with CHARGE Syndrome

- Success Story: Clear Passage Allowed Me to Resume My Adventures

- Emergency Small Bowel Obstruction Surgery in India

- An End to Bowel Obstructions

Diet

- How to Relieve a Bowel Obstruction: Diet Guide

- Recipes For Bowel Obstruction Patients

- Diet Guide for Avoiding Bowel Obstruction

- Diet Modifications to Help You Handle a Small Bowel Obstruction

- Digestive Health Guide

- Bowel Obstruction: Diet & Lifestyle Recommendations

- Minimal Fiber Diet for Digestive Disorders

- Nutritional Guidelines

- Transitioning to a Regular Diet from a Low or Minimal Fiber Diet

- Low Fiber Diet for Digestive Disorders

Bowel Obstruction | SBO | SIBO